Shocking revelation: Even the nicest teachers can unwittingly destroy the future of Roma children

We see teachers as dedicated and caring professionals who are guardians of social mobility and fair opportunities for all children. They hold the keys to the future, and we trust them to use them wisely.

However, the reality can be much more unpleasant. Ethnic discrimination in schools persists, as evidenced by research carried out in the Central European region by neuroscientist Emile Bruneau. In 2018, he visited Ostrava to discuss his hypotheses directly with people from the field – Miroslav Klempar and the Awen Amenca organization. At that time, his research was in the process of being born; Today, after his untimely passing, we have in our hands the results that confirm what Roma families have been experiencing for generations......................................................

See the dokument Dehumanization.pdf

The key to children's success at school? Trust and clear rules, new research among parents shows

A child's success at school is not only based on grades. It is crucial whether the family feels safe at school, understands the requirements and knows who to turn to for help. New research from 2025, which took place in six Czech cities, provides concrete instructions on how to bridge the gap between family and school.¨

The Parents

and School 2025 research report focused on everyday situations in which trust

between families and schools arises or disappears. The researchers conducted

in-depth interviews with parents and grandparents in Havířov, Chrudim, Louny,

Ostrava, Prague and Slaný. The aim was to find out what works in practice and

what, on the contrary, leads to segregation and school failure.

Here are four main pillars that, according to findings from the field, can fundamentally change the situation for the better.

1. Climate is more important than prestige

Parents often do not look for "prestigious" schools for their children, but for an environment where the child feels accepted. Research in Havířov has shown that if the school has a bad climate and the child experiences prejudice or bullying, the family often chooses to "run away" to another school, even if it has a worse reputation.

On the other hand, in Ostrava-Poruba, the so-called Welcome rituals. Class teachers organize "parent circles" in the first grade, where the norm of respect and the rule that "we are all in the same boat here" are set. Such a clear set of rules from day one builds trust and prevents conflicts.

2. "Safe person" directly at school

In many cases, for example in Slaný, parents said that they did not trust "anyone" at school or in the non-profit sector. This leads to problems not being addressed in time and escalating.

The solution is the institutional anchoring of the so-called Constitutional Court. safe persons. It should be a specific, named person (school psychologist, educational counsellor or employee of a non-profit organization) who has dedicated consultation hours and enjoys the trust of families. This person acts as the "first brake" to the escalation of conflicts and helps families navigate the system.

3. Communication and Support Cards

The language of the school and the authorities is incomprehensible to many parents. Parents often have no idea what support measures their child is entitled to or how the pedagogical and psychological counselling centre (PPP) works.

Research recommends the introduction of simple, one-page documents:

• Communication card: Clearly states what channels the school uses (Bachelors, email, phone), how quickly it responds and how to apologize if the family does not have internet.

• Support card: Explains clearly what an Individual Education Plan (IEP) is, how to apply for it and who is responsible for what.

4. Digital bridges instead of barriers

Compulsory electronic communication is becoming a trap. Some families do not have data or smart devices, and the school interprets their silence as a lack of interest.

Schools should offer the so-called Digital bridges – short practical workshops for parents where they learn how to control school systems. At the same time, there must be an agreed offline alternative, such as a telephone line with a guaranteed callback time or paper excuses.

Conclusion: From heroism to the system

The current system often relies on the "heroism of individuals" – committed teachers or persistent parents who act as advocates for their children. The aim of the proposed measures is to make fair access and support a standard that will not disappear with the departure of one enlightened teacher.

When schools and nonprofits put in place clear and predictable rules – from enrolment to dealing with absences – the chances that children will not only stay in mainstream education, but also succeed in it, increase.

Impact Chain Analysis: Desegregation Activity 2024 (NPI/AP D.H.)

The document maps the impact chain of the Czech desegregation program—from direct outputs to long-term learning outcomes—into a structure that supports decision-making.

It assigns evidence levels and probabilities to each stage, enabling clear prioritization and risk management.

It captures key assumptions and dependencies (legal basis, financing beyond 2025, municipal political will) and flags likely tensions (municipal/parent resistance, public polarization) with mitigation levers.

It provides concrete metrics and field data ready to convert into infographics, dashboards, and one-pagers for partners and donors.

Practically, it serves as an executive compass for MoE/NPI and city teams—and as a brief for EU-level talks—showing what works, where the risks are, and which levers to pull next.

!!! EU Risks Weakening Rights Protections in New Funding Rules !!!

The European Commission is finalizing rules for distributing EU funds for 2028–2034. Awen Amenca and the FURI coalition warn that the new proposal could weaken protection for Roma, people with disabilities, and others most at risk. While it mentions fundamental rights and civil society, key safeguards—like conditions against segregation and institutionalization—have disappeared.

Still Separate and Not Equal

Despite the Czech Republic's commitment in 2016 to fostering Roma children's inclusion in

mainstream education, progress has been tremendously low.

By Alice Millerchip and Emily Mason

31 January 2020

Denisa Gaborova remembers well the day her seven-year-old daughter, also called Denisa, came home from school crying. She had been told she could not attend a class field trip to a farm several miles from her elementary school. Her teacher said it was because there was no room on the bus, but it was only Denisa and the four other Roma children who were being left behind.

"She didn't want to go to the school that day," Gaborova recalled. "She said the teacher was mean, taking the other children and not 'us'." Although she has other examples of the teacher favouring non-Roma students, other students are given stamps and stickers as rewards for good work, but not little Denisa, she says. Gaborova wants to keep her daughter in a mainstream school, rather than sending her to one of the so-called "Roma schools":

"I want her actually not to be separate. I don't want her to be just with Roma". She said she wanted her to "Have a good education next to other children [and] be better prepared for high school, [and for] a better future."

That was the motivation for starting of a far-reaching reform initiative in the Czech Republic, which was launched in 2016 in an attempt to combat discrimination against Roma children in the education system. However, experts say that, so far, the reforms have failed to significantly improve things for young Roma, due to various dilemmas such as prejudice, poor teacher training, tradition and intolerances, and deeper unresolved issues such as housing issues which negatively impacts the progress.

At the same time, the sudden shift to "inclusive" schools and classrooms has been a challenge for teachers, with the potential to create negative attitudes toward inclusion overall.

Little To No Impact

As of 2016, Roma children were six times more likely than non-Roma children to be placed in special schools - separate schools in the Czech education system for children with mental disabilities - according to a European Commission report.

That report confirmed that discrimination was continuing almost a decade after the European Court of Human Rights found the Czech Republic guilty of indirectly discriminating against Roma children by channeling them to these special schools with the diagnosis "mildly mentally disabled." The court had ruled that Roma children were disproportionately represented in special schools and being taught to lower standards, thereby limiting their future educational and career opportunities.

Facing international pressure and criticism for not doing enough after the judgement in 2007, the Czech Republic acted after the European Commission report in 2016, amending its education law to curtail segregation. Yet, the 2016 reforms went even further than Roma inclusion and aimed to gradually eliminate special schools altogether so that children diagnosed with mild mental disabilities could be integrated into the mainstream system.

The government also introduced a compulsory year of pre-school education in hopes of increasing enrolment of Roma children. All these measures aimed to provide equal educational opportunities to all Czech children.

Yet three years after the amendments, Roma parents still find themselves subject to an arsenal of tactics to keep their children out of certain schools, according to critics. In fact, data from the ombudsman's office show that even without a diagnosis, Roma children still end up in separate schools. While only 2.3 percent of the Czech population is Roma, as of 2018 there were 13 primary schools with over 90 percent Roma students. The same report showed that children being educated according to a reduced curriculum (as a result of the "mildly mentally disabled" diagnosis) had decreased by only 1.6 percent since the Education Act was revised in 2016.

"Our conclusion is that the amendment of the school act in 2016 had no impact on segregation," said Miroslav Klempar, chairman of Awen Amenca, an organization aiming to integrate schools in Ostrava. "Not at all." "Former special schools" remain very much "un-abolished," and today serve as de facto Roma schools, Jindra Maresova, the director of Nadace Albatros, a Roma activist organization, said.

"It's a very low quality of education; not all of them - they really, really try - but mostly they are very poor quality," she added.

However, Maresova acknowledged that social pressures gear Roma parents toward these former special schools, not least because of a desire to protect their children from bullying. "[Pupils] are usually children of former pupils, so the parents know they [the teachers] are friendly and they would rather put their children into these schools."

The mainstream alternative can seem terrifying. In 2018, a Roma eighth-grader attempted suicide after being bullied at her primary school, TV Nova reported. "It began with insults because of what I look like and what I am. They said I am a 'shitty gipsy'," the girl said.

The Challenge of Mass Inclusion

It was not only Roma children that the inclusive education reforms targeted. Czech teachers are now responsible for teaching a mainstream curriculum to students of various learning abilities. While many educators agree that the reforms have increased financial support for educating all children, training teachers to deal with inclusive classrooms has been difficult.

Often, it is children with mental disabilities that pose challenges in the classroom - not necessarily Roma children - stressed Jana Strakova, an associate professor at the Institute for Research and Development of Education (IR&ED) at Charles University in Prague. And these challenges create negative attitudes toward inclusion as a whole.

"I think Czech teachers need help," she said. "Educators do not have sufficient expertise to educate heterogeneous groups of children, and they do not have sufficient help to do this.

"They do not know how to handle children with behavioural problems," she added. "They have the feeling that they are alone, and that they have no one to ask for help, which to some extent is true."

Various organizations, like the NGO People in Need (PIN) - one of the largest nonprofits in Central Europe -

offer training services to help teachers adapt to inclusive education measures. Tomas Habart, program manager of PIN's "Varianty" education initiative, said that around a decade ago, Czech teachers were fairly independent. However, with increasing demands since the education reforms, they do not feel prepared to teach inclusive classrooms.

"Now, they often feel like they are being attacked by parents, NGOs, and officials," Habart said. "Many of them feel like they have many more responsibilities but aren't getting enough support."

And although the new role of teaching assistant - introduced in the Czech Republic with the reforms - can provide help to teachers, finding candidates to fill these auxiliary positions is no easy task.

"Generally, the teaching assistant profession is not attractive to many people," said Jaroslava Simonova, who works with Strakova at IR&ED.

Teaching assistants are poorly paid in the Czech Republic, and the country has a very low unemployment rate. Further, the teaching assistant profession is not yet well-established in the Czech educational system, Simonova said.

This hiring problem has deep consequences. The lack of teaching assistants is one of the main barriers to inclusive education, according to principals of mainstream primary schools in the Czech Republic, cited in a 2017 Open Society Fund Report. The report analyzed the impact of the inclusive education reforms in their first year.

"The teachers are not very skilled in inclusive education at all," said Maresova, of Nadace Albatros. "Here there is a very short history of talking about being inclusive in education - this is something nobody taught them."

If teachers are provided with sufficient training and aid to cope with the challenges that come with inclusive classrooms, Strakova said, they will start to have more positive experiences. In turn, positive attitudes toward inclusive education may emerge.

A Vicious Circle

However, Strakova also acknowledged that the ingrained beliefs of Czech educators continue to hinder the inclusion of Roma children in schools.

"The problem is complicated and deeper than we realize because of the way Czech teachers perceive their task as educators," she said. "They do not feel responsible for every child. They only feel responsible for the children that 'deserve' it." Educators often categorize "deserving" children as those who come from families that care about education, she said. Many Roma children don't fit into this category, at least in the minds of their teachers.

"For some teachers, it's difficult to find some functional ways of cooperation with parents," Felcmanova said. "Racial prejudice is sometimes behind all these feelings toward Roma children, so it's a mixture of these [reasons]."

Within the school community, people think parents should be responsible for filling gaps in their children's education, said Lenka Felcmanova, vice president of the Czech Society for Inclusive Education, an NGO working to integrate Czech schools. But with 72 percent of Roma dropping out before high school, it's unrealistic to expect some parents to supplement their child's studies.

Zuzana Ramajzlova, project manager of PIN's social work program, works with families in excluded localities to provide them with educational and social support. Although she said the inclusive education measures have brought positive changes to schools in some areas, schools near socially excluded localities still struggle. For one, given the pressures of daily life, education is often not a priority for many Roma families living in socially excluded localities, she said.

Many of the Roma parents Ramajzlova works with only have an elementary school level of education themselves, and many are former pupils of special schools. Their negative experiences with school create a negative attitude overall toward the education system.

As a man of Roma ethnicity, Klempar from the Awen Amenca NGO regularly faced discrimination at school, despite being the smartest in the class. He recalled a particular experience in sixth grade when his science teacher was walking up to the front of the classroom.

"She passed me and said, 'It stinks in here. Oh, it's a gipsy.'" As a community organizer and advocate for quality education for all Roma children, Klempar said the Roma children he works with still complaining of similar encounters.

"We hear from the children about teachers coming to class and saying, 'You will be nothing, it's a waste of time for me to teach you,'" he said. "Some teachers are talking like this openly."

When teachers openly show prejudice against Roma children, the children are not motivated to learn, he stressed. Attitudes like this can provoke children to misbehave in the classroom, further fueling the stereotype that Roma children are disruptive.

"Roma children are demotivated to learn and can even be rude to the teachers," he said. "It's a circle, and in most cases, it starts with the teachers."

In Ostrava, the same eastern Czech city where Klempar works, Roma mother Denisa Gaborova says it can be near impossible for her to schedule a meeting with her daughter's teacher, and she often feels the conversations are unproductive.

"They are not harsh; they are not rude or anything. They are speaking politely because they know you can complain." Gaborova says. "You can feel you are a second-class citizen; they are speaking to you from on high."

Digging Deeper

If the government really wants to tackle the problem of discrimination, Simonova said, officials need to look beyond the educational system to other problems, such as housing segregation and Roma unemployment.

"I think the government took the [inclusive education] measures because it seemed easier to change something in schools," she said. "But the problem lies in the broader, socio-economic background of Roma children, and to solve that would be much more complex."

Around half of the Roma living in the Czech Republic are estimated to be "socially excluded," according to a 2016 Czech government report, cited by romea.cz, a Roma news site. Pushed to the outskirts of society, families

in socially excluded localities often face financial, employment, housing, and health difficulties.

Jaroslav Faltyn - director of the Department of Preschool, Basic, Basic Art, and Special Education at the Ministry of Education - argues that it is social factors, rather than legislative obstacles that keep Roma students separate. He called for "complementary cooperation" from departments outside the Ministry of Education.

"This is, rather, a social problem," he said. "In the education segment, we have fixed, I would dare say, all the things we can fix as representatives of the education segment.

"How many vulnerable children [are] coming from families with alcohol, drugs, drug abuse from a very early age, during pregnancy, during early childhood?" he asked. "Imagine that these children are coming from families where there are sources of very serious health problems."

The Ministry of Education made one year of preschool mandatory in 2015 to combat low enrollment rates among Roma. However, most Czech students attend preschool for three years and enter primary school able to read and count. Meanwhile, Roma children with only one year are far behind, leaving teachers frustrated.

But even with the preschool programs, many Roma parents do not enrol their children to protect their children from hostility in schools.

"You don't want your small child to face racism and hostility," Klempar says. "So the Roma parents would rather have their child at home as long as possible."

Meanwhile, Faltyn emphasized that some Roma parents were not necessarily avoiding the "former special schools," either. Although the 2016 reform allowed children in special schools to be retested if unsatisfied with their results, he said that many Roma parents do not take their children to be re-evaluated.

"It's important to motivate families so they can support their children," Ramajzlova emphasized. "Cooperation between the education system and social services is necessary to really improve the situation."

Klempar's organization, Awen Amenca, has seen some success enrolling Roma children in mainstream schools by educating parents on their rights and the benefits of mainstream schools. The organization advises every parent to insist that schools accept their applications so that they have to reject the student formally, which can then be appealed. The organization also sends out a list of enrollment dates for the mainstream schools.

Martin Klener is a teacher at a groundbreaking elementary school in Trmice, located on the outskirts of Usti nad Labem, an industrial city in north Bohemia. He has found cooperation between schools and parents to be important for positive student outcomes.

"Sometimes there are parents who are afraid of sending their children to school because they think teachers are enemies and that we are hurting their children," Klener said. "When we persuade the parents that it's important for them to send their children to school, it's halfway to a win."

Pushing Children - to Succeed? Or Pushing Them Out?

Many non-Roma parents also resist inclusive measures because the education system seems to work fine for their own children. Because of this resistance to change, there is often little effort on the side of municipalities to push for inclusive schools.

At the same time, PIN's Habart said: "There is a demand from a significant part of the voters for segregation, which influences municipalities.

"There is the central vision of the Education Ministry but there is also a lot of power at the local level, which sometimes goes against the central strategy."

Klempar and Gaborova also report a slew of tactics to keep Roma children out of schools, including asking for money upfront with the school application, which is restrictive for low-income parents; claiming that the school is at capacity; not accepting applications; only accepting online applications, and hiding the enrollment dates for mainstream schools from Roma parents.

"The biggest obstacle is that the schools are always trying to find some ways to get rid of Roma children," says Klempar.

At the same time, advertising the enrollment dates for segregated schools never seems a problem in Roma neighbourhoods. "There are posters all over the excluded localities on every corner, and in every shop, there are fliers for segregated schools everywhere in the excluded localities," he added.

Klener's school in Trmice is an outlier in pioneering inclusive education. The school, where one-third of students are of Roma ethnicity, has gained national recognition for its inclusive efforts. The school welcomes children of various backgrounds, non-native speakers, and kids with disabilities. As early as 2015 - even before the national reforms - the school's principal, Marie Gottfriedova, was presented with an award by the U.S. Embassy in the Czech Republic for her success in implementing and advocating for inclusive education.

"I am convinced that the principal plays a key role in the methodological support of teachers," Gottfriedova said. "It should be clear about the educational vision of the school, what the pedagogical accents of a particular school are, what the educational goals are, and what steps [need to be taken] to achieve these goals."

It is Gottfriedova's leadership and support that Klener, who has been teaching at Trmice for 15 years, credits as the reason for the school's success with inclusive education.

"Our principal and former principal are not afraid of making changes," he said. "They want us to move forward."

Of the 19 students in Klener's classroom this year, four are of Roma ethnicity; three have learning disabilities; one has spinal muscular atrophy and is in a wheelchair; and one, who is Vietnamese, has been working to improve his Czech-language skills with a teaching assistant. Around seven of his students are socially deprived in some way.

Klener explained that tailoring teaching methods to cater to all children, regardless of their ability or background, is something that teachers at Trmice do well.

Working in groups has helped his students learn from one another, he said, but stressed, "Each class is different. Something that works in one class doesn't necessarily work in the second one. And when something doesn't work, it's important to not be afraid. Instead, we must try to find different strategies."

Alice Millerchip is a recent graduate of journalism and international relations at the University of Richmond, with bylines at the Henrico Citizen and Richmond's Capital News Service. She attended TOL's "Going on Assignment" reporting course last summer. Emily Mason is a junior journalism and English major at New York University, with bylines at amNewYork, Straus News, and Washington Square News. She was a TOL intern last semester.

A Survey on the needs of Roma children enrolled to good quality primary schools in Ostrava from January 2014 until January 2015 and identifying the difference in the quality of education among the basic primary schools and segregated primary schools

Different educational outputs in relation to continuation in secondary education and the differences between segregated and non-segregated schools.

Understanding Why Teachers Discriminate Against Minority Students

Teachers in Hungary are more likely to discriminate against Roma students than non-Roma students.

By Ashton Yount

Teachers spend their time educating young people, imparting both intellectual knowledge and practical life skills, in an attempt to help children grow into adults. They often do this for low pay and little thanks. They are the best of us, or at least they're supposed to be.

But teachers are regular people, too. And regular people have biases that sometimes inhibit their abilities to do their jobs.

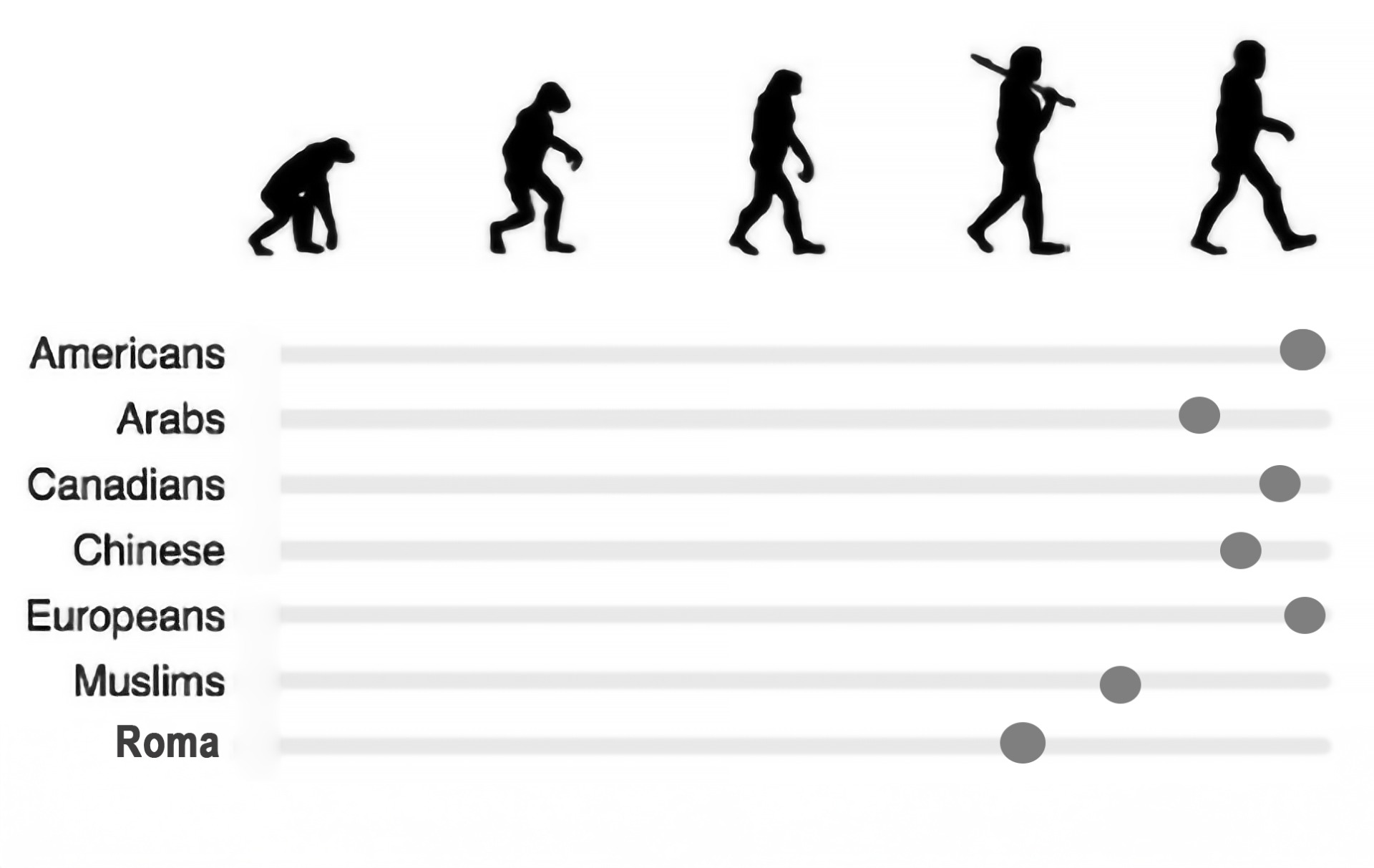

A new study authored by Research Scientist Emile Bruneau found that teachers in Hungary are more likely to recommend Roma students for the lowest-track secondary school, as compared with non-Roma students. The study also found that this is due to blatant dehumanization — thinking another group is less evolved and/or civilized than your own — rather than affective prejudice, which is disliking people belonging to a particular group. In fact, the study shows that teachers with the lowest levels of prejudice were most likely to discriminate against Roma students when placing them in secondary school tracks.

"Teachers are a very interesting group to study because they tend to be very caring, prosocial people, and are the guardians of social mobility," says Bruneau, Director of the Peace and Conflict Neuroscience Lab. "So we thought that this might be a case where more subtle or implicit biases would be driving the behaviors, rather than blatant dehumanization. But we found the opposite."

Bruneau and colleagues recruited Hungarian teachers in training and asked them to evaluate profiles of 8th grade students to decide whether the students should be placed in the low, middle, or high secondary school track. Unbeknownst to the teachers, the researchers created the profiles to represent relatively equally qualified students and then assigned each with either a typical Roma name or a typical non-Roma name.

The teachers consistently placed equally qualified Roma students into lower tracks than their non-Roma counterparts, thereby giving better opportunities to non-Roma students and curtailing Roma students' educational possibilities.

"Education, of course, is the number one way that you can improve your social rank in society," Bruneau says. "In Europe in particular, the system is such that the secondary school you are placed in is hugely consequential. If you're placed into the lowest track, even if you do great in secondary school, you're not eligible to go to college.

In order to understand why the teachers discriminated against Roma students, the researchers next asked the teachers to complete a series of questions designed to measure blatant dehumanization, subtle dehumanization, and general dislike of the Roma. The researchers found that subtle dehumanization and general dislike did not predict the likelihood of discrimination, but blatant dehumanization did.

If teachers felt that the Roma were less evolved and civilized than non-Roma, they were likely to place Roma students into the lower educational tracks, regardless of their general like or dislike of the Roma. In fact, the teachers that were most likely to place the Roma students into lower educational tracks felt great warmth toward them while simultaneously considering them less evolved than non-Roma students.

The researchers point out that this type of dehumanization is associated with paternalism; it's the type of dehumanization that results in policies like the forced removal of Indigenous children from their families to educate them in western-style boarding schools. In the case of this study, the teachers likely felt they were "helping" the Roma students by placing them in the lowest educational track.

"These types of behaviors are hard to explain," Bruneau says, "because they seem to be motivated by general caring, yet they're just as damaging to a population as outright hostility is. This study helps us begin to understand the psychological profile that is necessary to both feel warmly toward a population and think of them as less than human."

Bruneau hopes this study will help guide future interventions for teachers. He says rather than focusing training solely on prejudice reduction, as is typical, we need to find a way to change perceptions about the essential nature of marginalized populations.

"In every country we've studied," says Bruneau, "we've found at least one marginalized group that people report blatant dehumanization towards. Through our research, we hope to continue to chip away at erroneous perceptions that people around the world have and apply scientific principles toward peace."

"Beyond Dislike: Blatant Dehumanization Predicts Teacher Discrimination" was recently published in Group Processes & Intergroup Relations. In addition to Bruneau, authors include: Hanna Szekeres, Eötvös Loránd University; Nour Kteily, Northwestern University; Linda R. Tropp, University of Massachusetts Amherst; and Anna Kende, Eötvös Loránd University.

Training manual on community organizing

WHAT IS COMMUNITY ORGANIZING?

A process by which people are brought together to act in common self - interest and in the pursuit of a common agenda. Community organizers create social movements by building a base of concerned people, mobilizing these community members to act, and in developing leadership from and relationships among the people involved. Organized community groups seek accountability from elected officials, corporations and institutions as well as increased direct representation within decision - making bodies and social reform

A key pilot study on Roma children in UK schools, conducted around 2011, found that while UK schools offered welcoming, less discriminatory environments compared to Eastern Europe, leading to better integration and pupil/parent satisfaction, attainment was often average or slightly below average, highlighting challenges with low starting points, language barriers, and disrupted education, prompting recommendations for better integration strategies and challenging segregation in other countries. More recent UK initiatives (2021) poured £1 million into Gypsy, Roma, Traveller (GRT) programs to boost attainment, reduce dropout, and support families, acknowledging persistent disparities.